Not long ago, I heard John Risley interviewed on CBC about his collection of Maud Lewis paintings, and I was struck by how human he seemed. I was used to Risley being parodied in the media for his insatiable greed, but this report gave him artistic sensibilities, even a community spirit when he discussed his wish that the collection be donated one day to a museum.

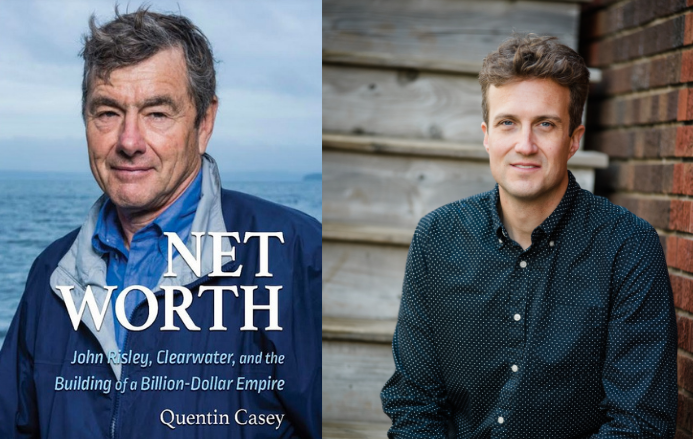

Turns out, Risley is indeed a living and breathing, (and investing and spending) human, who Quentin Casey has done a brilliant job of bringing to life in the pages of Net Worth: John Risley, Clearwater and the Building of a Billion-Dollar Empire.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Net Worth: John Risley, Clearwater and the Building of a Billion-Dollar Empire

By Quentin Casey

Nimbus |359 pages | $34.95

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Most of us know Risley through descriptions in the Halifax media, which tend to portray him as something akin to Ebeneezer Scrooge, but without the warmth. Within Casey’s deft prose, Risley is a workaholic, driven to make and spend as much money as he can, even in his seventies. He’s difficult. He yells a lot. The trappings of his wealth include superyachts, private jets and mansions (the plurals are intentional). But he’s also witty and has a softer side. He lets picnickers use his beach and is generous to his friends. When he arrived at a remote airport once and learned a woman was in labour, he had her flown by his private plane to the nearest hospital. (She ended up calling the baby John.)

The other gazillionaires who Casey interviewed think the world of him – all of them, that is, except possibly Colin MacDonald. He's Risley’s ex-brother-in-law and ex-business partner. The partnership ended badly, with MacDonald blaming its demise on Risley’s greed, spending, and reluctance to collaborate on important decisions.

But for several decades, they were a dynamic force in Canadian business. Risley was the visionary and wheeler-dealer, while MacDonald was a master of operations. Beginning in 1976, they changed the Atlantic Canadian seafood industry, by breaking into new markets in Europe and Asia and pioneering the use of on-land tanks for storage of live lobsters. These tanks allowed Clearwater to buy lobster during the lobster-fishing season when supply was high and prices low, and sell in the off-season, when the reverse was true.

Writes Casey: “Clearwater had started as a small retail shop but to succeed it had to become more than a simple seafood company: it was a technology company; a logistics company; a distribution company; a science and research company; and, eventually, a harvesting company too.”

One of the most interesting chapters of the Clearwater story is the final one, when the company was taken over for $1 billion by a partnership between Premium Brands and a group of Mi'kmaq First Nations. Setting aside the dollars and cents of the deal, this was an important act of reconciliation because it allowed the Mi'kmaq to once again harvest from the ocean.

While the story of Clearwater is interesting, the chapter that will be of most interest to Entrevestor readers will be the portion on Ocean Nutrition Canada. Launched in 1997, the Dartmouth-based company turned Omega-3 fatty acids into food ingredients. Fifteen years later, Royal DSM of The Netherlands paid $540 million for the company.

The ONC story was well known before, but Casey does a great job of fleshing out the story. It had been Risley’s baby from the word go, and MacDonald wasn’t that involved, even though their joint investment company sank $35 million in it. (Not a huge investment when you consider Risley has invested $65 million into Skinfix, the company headed by his second wife Amy.) ONC ventures lost money for years, and there were hard feelings when CEO Robert Orr was replaced with Martin Jamieson.

While the Risley-MacDonald partnership did well off Clearwater and ONC, they really cashed in on Columbus Communications, the Caribbean cable and telecom company that Risley set up with St. John’s businessman Brendan Paddick They sank US$50 million into that venture and eventually spun it into a fortune by selling out first to the stodgy British company Cable & Wireless for US$3 billion in cash, stock and assumed debt. They cashed in again when Cable & Wireless sold out to t Liberty Global for US$7.4 billion.

It was a huge windfall, but it was also one of two contributing factors that brought the relationship between Colin MacDonald and John Risley to a head. (The other was Risley’s divorce from MacDonald’s sister Judi.) While Casey does a great job of bringing out Risley’s personality, it’s MacDonald’s meat-and-potatoes persona that leaps from the page. MacDonald’s irreverence, candor and f-bombs breathe life into what was already a splendid book, and the reader forgets (just for a second) that this is a guy worth comfortably into nine figures.

My lone quibble with the book is that it doesn’t discuss Risley's role as a super-angel. He has invested in several Atlantic Canadian startups and even exited from Kinduct. But it’s a part of his business activities overlooked in this book.

Risley and his circle all co-operated on the writing of the book, and Casey did an impressive job of getting information from them – both in terms of the details of the businesses and the human relationships. Net Worth will stand for a longtime as the essential study of the region’s most important businessman.