One of the highlights of 2019 for me was transcribing a bunch of old family papers, including correspondence from the First World War when my grandfather and his brother were artillery officers.

Each Remembrance Day, I always think of my grandfather H.P. MacKeen, and his service in the Great War. This year I know more about his time overseas than ever before because I went through his letters from the front.

I already knew Harry, as he was known, fought at such battles as Ypres and Passchendaele as a Major with the Royal Canadian Artillery, and that in 1916 he suffered shell shock so severe he had to be hospitalized in England. But this year I went through his papers and found what’s survived of his letters from the front.

Only about a half dozen of his letters from the war survive, as well as one or two from his brother David. As most soldiers do, he edited what he wrote to his mother. He was more candid to others, like his sister Marjorie. Though his letters to her are lost, we have her response of July 8, 1916 after he’d written her. “I cannot tell you how thrilling your last letter was – I mean the one written to me with such graphic descriptions of that ghastly battle,” she wrote. “It simply made my hair stand on end while reading it.”

He had told her his letters to their mother were less graphic, and she agreed he had to protect their mother from the truth of his ordeal. They both agreed he should tell her just enough about the battles that she would not suspect he was holding anything back, but he should spare her grisly details.

The main thing I learned from his letters was his role in the gun crew. I remember once in the late 1960s Harry explained to me the different jobs everyone had within a gun crew, but I was too young at the time to take it in.

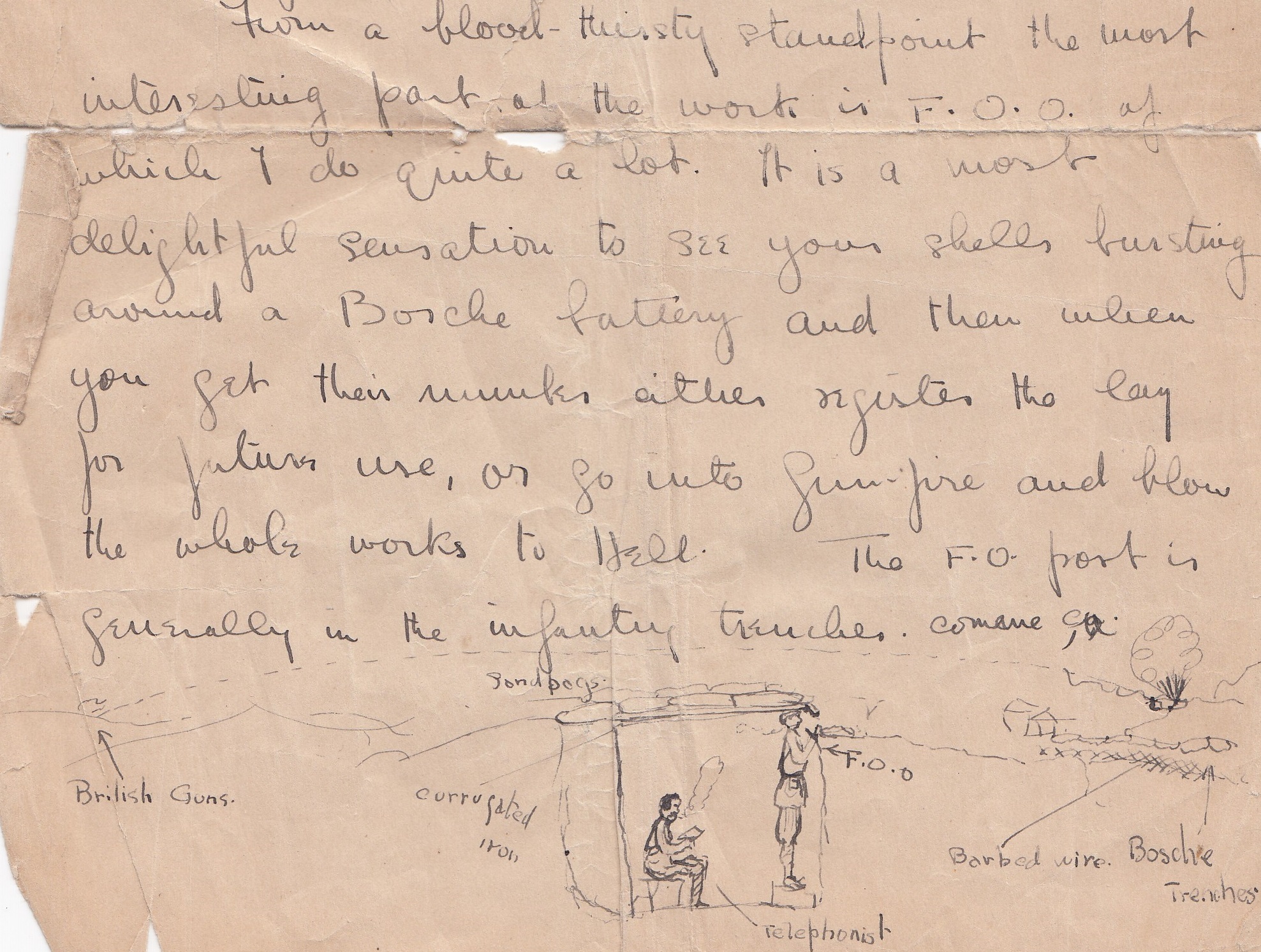

In one letter home (undated as the first page was missing), Harry explained that he was a F.O.O., or a Forward Observation Officer. The gun crew set up behind the trenches, where they would shell the German positions, often without being able to see their targets. The F.O.O. (viewing the field of battle through binoculars) and a signaler would be located in the trenches, ahead of the gun battery, to monitor where the shells were landing. Once he saw the shells land, the F.O.O. would have the signaler radio back to the gun crew telling them how to adjust their aim to zero in on the objective.

Harry included a little cartoon at the bottom to illustrate the positioning of the F.O.O. Throughout his life, he continued to include cartoons in the margins of his letters, usually amplifying some joke in the text.

Early in the war, Harry gave the impression he enjoyed being a F.O.O. and witnessing the explosions, but it was dangerous work and Harry saw too many signalers die.

“I lost my best signaler the other day, Sgt. Oakes,” he wrote to his mother on Nov. 17, 1917. “He was on O.P. duty at the time. He was a fine fellow and the last survivor but one of all the signalers [who] were brought from Halifax. They are a very hard lot to replace. They were a dare-devil crowd and absolutely the last word in anything to do with signaling or O.P. work and the best lot in the world to work with.”

Harry survived the war, but he suffered from PTSD well into the 1920s. He overcame it and had a successful career as a trial lawyer, becoming Lieutenant-Governor in 1963. I was only 10 when he died, but his impact on me was huge.

A few cartons of his papers had been sitting in a crawl space in my house for years, and this year I finally went through them and took them into the Nova Scotia Public Archives. They’re now preserved for posterity. It seems fitting to remember Harry on the day when we salute the heroism of the millions of people who served.