With emergency services organizations recovering from two years spent operating in a state of crisis, the chief executive of Halifax startup ELi Technology believes the time is right for a major sales push.

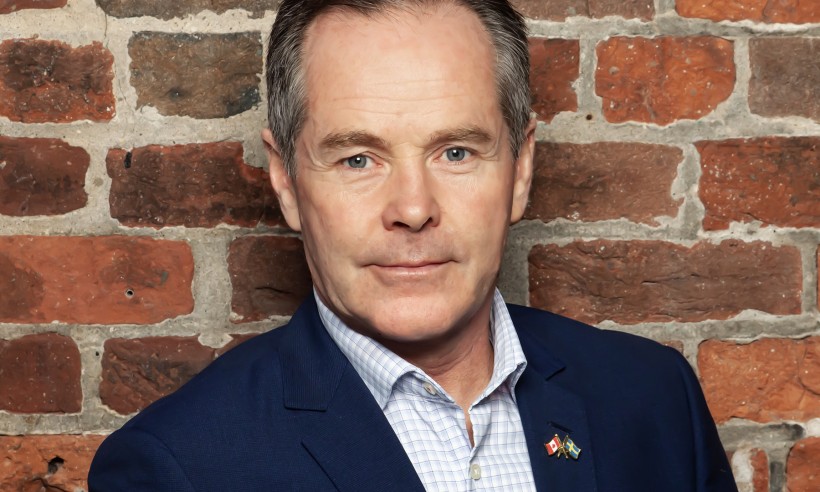

Peter Woodford founded ELi in 2017 and aims to replace conventional 911 systems that rely on antiquated phone networking technology with his company’s more accurate, internet protocol-enabled Emergency Mobile Location, or EML, methodology. He said in an interview that EML’s main advantage is its ability to offer 911 operators the precise location from which a call originated, rather than merely a broad search area.

Many emergency response organizations have faced abnormally high call volumes and record absenteeism since the beginning of the pandemic, leaving them unable to consider buying new technology, Woodford said. But with the public health situation normalizing across much of the developed world, the market is proving increasingly receptive to ELi’s sales pitches.

“A lot of the management team that would be looking at doing new projects were being distracted because of the crisis that their industry is under,” said Woodford.

“But now, as the pandemic’s transitioning into an endemic … the stress is coming off the system, and now they're looking at ways to improve and make things better.”

ELi has two sales units. One focuses on selling to governments and the other to non-governmental organizations, such as universities, that are responsible for protecting the safety of people within a given geographic area.

Woodford expects ELi’s first sales revenue to arrive within weeks. His team has added 28 companies to a list of possible international distribution partners and is pursuing sales prospects numbering in the double digits on both the governmental and private-sector sides.

And although there are other companies that provide location services for 911, Woodford said ELi is the only player in the market that can offer first responders an exact location — particularly in indoor environments like apartment buildings, where conventional systems cannot direct responders to individual units if the caller is not using a landline.

ELi’s EML methodology is compatible with existing emergency call protocols on smartphones and even apps such as WhatsApp.

When the user of a modern smartphone dials 911 or analogous emergency numbers in other parts of the world, their phone automatically turns on its GPS services and scans for nearby Wi-Fi networks. If a region is using ELi’s system, that information will then be sent to the company’s servers, where an API will translate it into a format compatible with existing 911 infrastructure.

The combination of GPS data and information about surrounding wifi networks allows ELi to exactly pinpoint the location of a caller’s smartphone, including the civic address, floor number, apartment number, latitude, longitude and altitude. By contrast, existing systems can usually only offer a search area of about 50 metres.

“The advantage of having an Internet Protocol system is that, in the legacy system, you are only really able to provide a voice with a phone number,” said Woodford. “In a next-gen system, because it's IP-based, an abundance of additional information can be made available.”

He said the process of trying to locate a 911 caller adds an average of about 30 to 90 seconds to emergency response times in North America.

So far, the company has 12 employees and Woodford is planning to hire more in the coming months, although ELi does not currently have any job openings posted.