It’s a little-known fact that IBM’s R&D team for cybersecurity is headquartered in Fredericton — all because of a transformative exit announced in 2011.

IBM that year agreed to buy Q1 Labs, a Waltham, Mass.-based IT startup that had begun in the New Brunswick capital a decade earlier. Q1’s chief technology officer Sandy Bird now heads IBM’s research into the fight against cybercrimes from his lab in Fredericton, from which he oversees 20 major R&D labs around the world.

The 2011 exit of Q1 Labs demonstrates perfectly how a local or regional economy can benefit when a local startup is acquired by a multinational. Since 2011, Fredericton has become a centre for cybersecurity tech development, as IBM has grown its team and new startups like Beauceron Security have launched. The Canadian Institute of Cybersecurity has opened at the University of New Brunswick and the provincial government has made cybersecurity a pillar of its economic development strategy.

This is just one indication of the importance of startup exits in economic development.

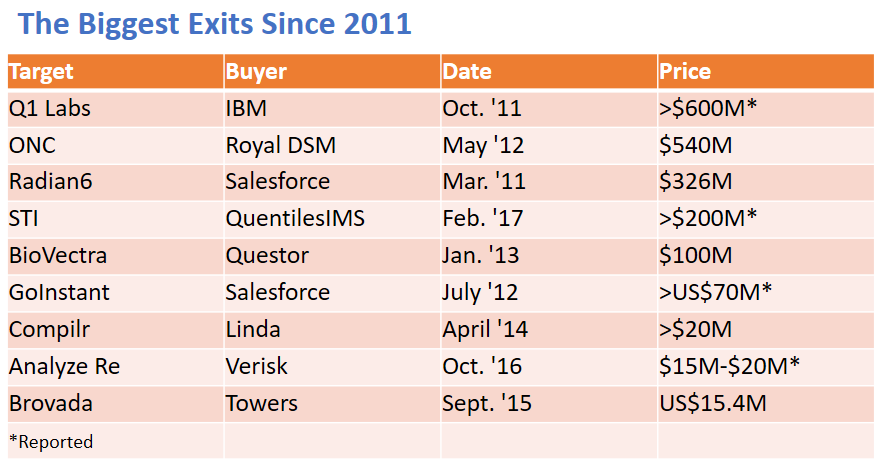

Entrevestor on Wednesday released its latest report on the metrics of Atlantic Canada’s startup community, and we featured special research into exits in Atlantic Canada. We found that there had been 27 startup exits since 2011 — that’s the year that Fredericton-based Radian6 was bought by Salesforce.com, the deal that really launched the startup movement in the region. We estimate these deals in total were worth at least $1.8 billion.

Novacap Buys Majority Stake in Leading Edge

The overwhelming majority of these acquisitions resulted in operations continuing in Atlantic Canada and growing their workforce in the region. We estimate there are now 2,200 Atlantic Canadians working for exited startups (including startups that exited before the Radian6 deal).

The benefits of exits extend beyond employment and include financing of other startups: Groups like Saint John-based East Valley Ventures, P.E.I.-based Island Capital Partners and St. John’s-based Killick Capital have used exit proceeds to back other startups. New investors like Halifax’s Jevon MacDonald and Patrick Hankinson are investing in companies because of the proceeds of exits.

As for the startup ecosystem, groups like Volta Labs in Halifax, Venn Innovation in Moncton and the pan-regional IT accelerator Propel ICT all were launched or received an early boost because of exits. Exits can even help to shape economic policy, such as the example of cybersecurity in New Brunswick mentioned above.

This research is important because exits are still discussed in policy circles in hushed voices, if at all. The thinking in some circles is that exits are great for the founders and investors, but the multinational buyers end up moving the operations to larger centres, taking jobs and technology with them.

The evidence simply does not support that theory. Exits are highly effective examples of direct foreign investment because the corporate buyers are usually acquiring proven teams with a rare combination of talent and technology.

It’s hard to find that combination (especially talent) so after purchasing the company the buyer is incentivized to grow the team, in its current location, and not screw things up by moving operations.

Government programs often aid this growth but there is no policy I know of that lays out how government departments and agencies can help founders as they are exiting. That should change. Development agencies should have transparent policies that tell business owners: If you’re selling your companies, let us help you welcome the buyer and grow the company after the sale closes.