The Atlantic Canadian group putting together the pitch for the oceans supercluster is reaching out to startups and small businesses, promising them a role in the ambitious scheme.

The steering committee this week has held information sessions in St. John’s and Dartmouth, with more than 150 people attending each session. The message has been two-fold: first, the oceans supercluster could be a huge opportunity for Canada and its East Coast; and second, small, innovative companies will be needed to provide solutions to industries that toil in salt water.

The idea of a maritime industries cluster has been gaining steam for several years. It received fresh impetus this year when the federal government said it would spend as much as $950 million over five years to support “superclusters” of innovation across the country. Atlantic Canada’s proposal of an oceans supercluster made the shortlist of nine finalists, and organizers hope it will be one of the three to five proposals to divide the federal jackpot. The final submission is due Nov. 24.

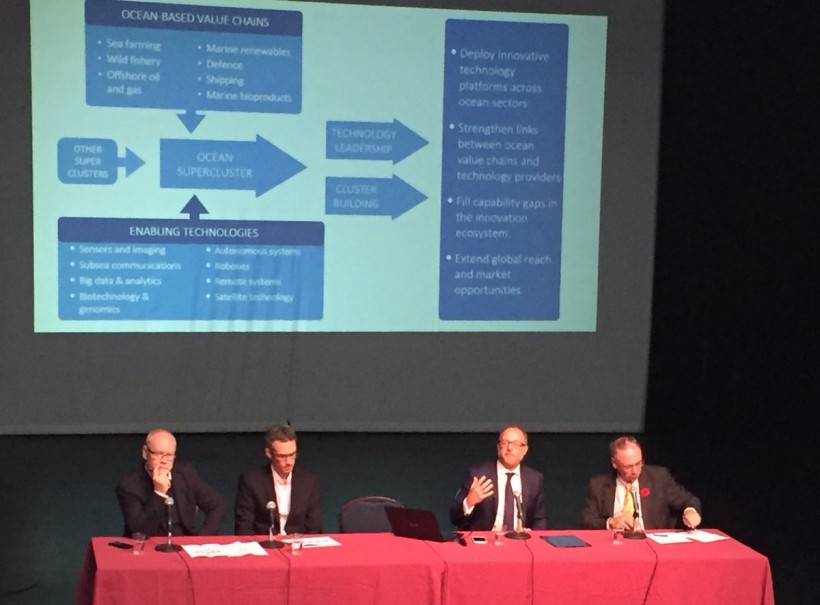

The committee envisages a structure that would encourage innovators to provide solutions to problems common to all ocean-related endeavors. Startups and other SMEs would be integral to devising the solutions – especially digital solutions, such as data-analytics products – that could be adapted by companies in Canada and elsewhere.

“Digitization is coming,” said Jim Hanlon, CEO of the Halifax Marine Research Institute and a member of the committee. “The ocean economy is actually late coming to it. ... The question is, How do we bring these capabilities to the supply chain?”

Ocean Executive Prepares for Launch

The information session revealed an oceans cluster structure comprising three layers of participants. At the top is a group of major private investors, which is now made up ofClearwater Fine Foods and the electricity company Emera, both of Halifax; Petroleum Research of St. John’s; and investment firm Cuna Del Mar. Below this segment are: other corporations involved in oceans-related businesses; and institutions that support research and the ecosystem.

The organization must come up with at least $125 million in private investment, which will be matched by the federal program. The group, which will probably have bases in all four provinces, will then channel the money over five years into a series of projects that will advance ocean-related industries.

Hanlon and other committee members stressed that startup founders have difficulty connecting with boardrooms of large corporations; and big companies also are perplexed by the challenges of developing innovation. The supercluster organization could improve communications channels for both groups, they said, as in would include “technology brokers” to connect projects and innovators.

“This is an opportunity to bring your company, from an SME perspective, into a whole new market,” George Palikaras, the CEO of the Halifax startup Metamaterial Technologies Inc., said during the Q&A session. “This platform lets us expand – the big companies are basically opening up the channels to us.”

That’s not to say there wasn’t some skepticism at the Dartmouth session. One participant noted that the strength of the Quebec aerospace cluster was its capacity to manufacture airplanes and asked: “Where’s the plane here?”

NS Awards Funding to Nine Oceans Projects

The fact is there’s nothing akin to aircraft manufacturing here. Such a manufacturing cluster brings a range of players together in a single supply chain, but the oceans cluster isn’t a single supply chain. It comprises seven different sectors, ranging from aquaculture to offshore oil and gas to marine shipping.

Hanlon and the other committee members – Matt Hebb of Dalhousie University, Christian Richard of Emera; and Dave Finn of Petroleum Research – said repeatedly they thought initially such a fragmentation would be a weakness in their scheme. But the more they dove into it, the more they considered it a strength. All these industries – united only be the fact that they operate in the ocean – face common problems and can improve profits by collaborating to find solutions, they said.

“It’s a bit of a challenge to bolt this one together, but if can pull it together it will be even more disruptive,” said Hanlon.

Hebb said ocean industries account for 2.5 percent of the global economy, but in Canada that figure is only 0.7 percent, even though the country has the longest coastline in the world. In Norway, for example, ocean-related industries account for 7 percent of GDP. The committee argues that the entire country could gain greatly by increasing the percentage of national output derived from ocean industries.

One audience member asked what Plan B is if Atlantic Canada doesn’t win supercluster funding. The panel members said Ottawa has been working to find other funding sources for worthy entrants that didn’t make the short-list. However, the group does not want to settle for consolation prizes.

“It’s ours to lose,” said Hanlon. “We have to find ways to work together that are non-traditional, but if we can do that we can bring in back home to Atlantic Canada.”