A giant in the field of entrepreneurship came to Halifax last Friday to give educators some schooling on how to build entrepreneurial ecosystems.

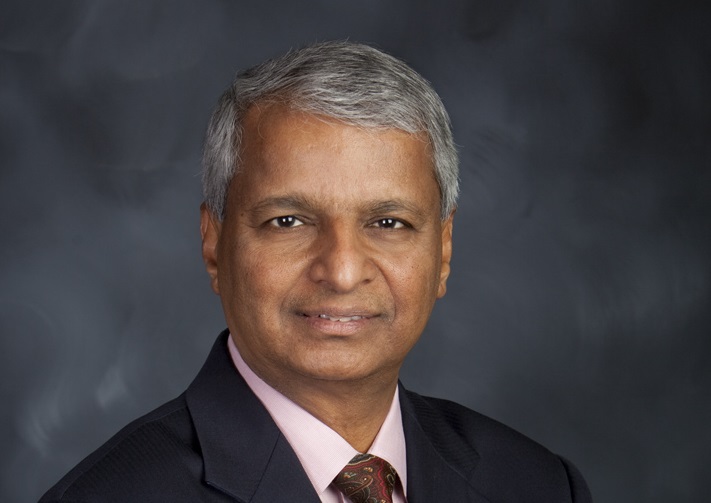

Entrepreneur, philanthropist and University of New Brunswick grad Gururaj Deshpande was the keynote speaker at the 2017 Global Consortium of Entrepreneurship Centres (GCEC) Conference last Friday at Dalhousie University in Halifax. And he delivered fascinating insights in how to develop ecosystems in two worlds he knows well — developed countries and developing countries. In both cases, he said, the goal is to nurture innovators who will have an impact.

In a university setting in the developed world, he said, the key is to ensure there is an entrepreneurial culture among students and faculty before creating myriad programs. The reason entrepreneurship has caught on so thoroughly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — where he founded the Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation — is that the student body teems with business-minded scientists.

“Don’t put the fuel in before you see the spark,” he advised the gathering. “You’ll just put out the fire.”

The GCEC is a meeting place for university entrepreneurship facilities from around the world, especially the U.S., and its mission is to help educational institutions aid students who want to launch businesses.

Deshpande, known to his friends as Desh, is an authority on the subject. A billionaire tech entrepreneur, he has founded or co-founded entrepreneurship centres in Boston, Fredericton (home of the Pond-Deshpande Centre), Kingston, Ont., and India. The Deshpande Foundation strengthens ecosystems that create significant social and economic impact through entrepreneurship and innovation.

Dal Aims to Double Female Computer Science Students

A native of India, he drew a distinction in his keynote between developing ecosystems in developed and developing countries. In developed economies, incubators must embed innovators in real world situations to make sure their ideas have relevance. The goal is to remove scientists from their bubbles to make sure they’re developing products for the market and not just to win plaudits from their peers. “The whole idea of the Deshpande Centre at MIT is to . . . connect people to relevance up front as they are creating the idea,” he said.

In the developing world, Deshpande said, you have to begin with relevance and then bring innovation in second. What that means is that there is a need to imbue the broader population — those who understand the community’s problems and culture — with an entrepreneurial spirit so they can devise ways to find solutions to their problems. Once there is an entrepreneurial spirit in the community, introducing innovation can help to improve the living conditions of the community.

Deshpande speaks of “building capacity in the community,” such as the Deshpande Foundation India, where 500 people at a time can go through a four-month program to learn entrepreneurship. The goal, he said, is to make a broad swath of the population understand they can solve problems instead of complaining about them.

“Just make people transform from being complainers to being problem-solvers,” he said. “Then it becomes fashionable and everyone is looking for problems to solve. When you have all these entrepreneurs looking around for problems to solve, no problem is going to hang around for too long because there is always someone who is going to grab it.”